There’s a certain warmth that only exists in a provincial kitchen at four in the afternoon. Rice is already steaming, the last sun of the day slides in through a capiz window, and somewhere a lola is crushing garlic with the side of a knife, telling a story with every tap of metal on wood. You can hear the sea if you listen closely—a distant hush behind the clatter of plates. This is where many Filipino island cooking traditions begin: not in restaurants or recipe books, but in these lived-in, salt-tinged kitchens tucked all over the Philippine islands.

In this piece, we’ll sit quietly in the corner of those kitchens. We’ll watch how Filipino heirloom recipes are passed on “by feel,” how adobo changes personality from island to island, and how family cooking rituals turn ordinary afternoons into something sacred. We’ll also look at how modern life and migration tug at these traditions—and how, despite everything, they keep finding new ways to survive.

What Island Cooking Traditions Mean in the Philippines

Cooking in an Archipelago of a Thousand Flavors

When we talk about island cooking traditions in the Philippines, we’re really talking about hundreds of small worlds. Filipino cuisine is already an umbrella term for the foodways of more than a hundred ethnolinguistic groups scattered across over 7,600 islands, shaped by Indigenous roots and later Chinese, Spanish, and American influences. Under that umbrella, every shore, river valley, and mountain town brings its own twist to what ends up in the pot.

When we talk about island cooking traditions in the Philippines, we’re really talking about hundreds of small worlds. Filipino cuisine is already an umbrella term for the foodways of more than a hundred ethnolinguistic groups scattered across over 7,600 islands, shaped by Indigenous roots and later Chinese, Spanish, and American influences. Under that umbrella, every shore, river valley, and mountain town brings its own twist to what ends up in the pot.

Geography does a lot of the deciding. Coastal barangays lean heavily on the day’s catch and preserved fish, coconut milk, and seaweed. Upland communities rely more on root crops, freshwater greens, native chicken, and whatever grows in the backyard. What does island cooking look like in a small Visayan town? It might mean early mornings at the fish port, kinilaw made while the fish is still practically glistening from the sea, and big pots of soupy stews that stretch one kilo of isda into a meal for a whole household.

Heirloom, Lutong Bahay, Lutong Lola

In Filipino homes, we often use words like “lutong bahay,” or “lutong lola,” for dishes that feel like they belong to the house itself—a kind of edible handwriting of the family. “Heirloom recipes” and “ancestral recipes” might sound formal, but they describe the same thing: dishes that have been cooked in almost the same way across generations, carried not only in memory but in muscle, habit, and taste.

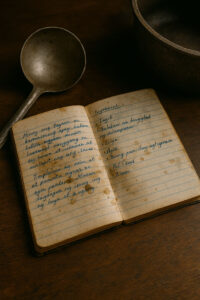

These island cooking traditions become a kind of archive. In a tangle of handwritten notebooks, in a mother’s reminder to “huwag masyadong haluin, masisira ang gata,” in the way someone reaches for patis instead of salt—you find the story of a place. Articles like Filipino food culture stories trace these layers at a national level, but here we’re zooming in: into the steaming, noisy, garlic-scented details of everyday kitchens where these traditions actually breathe.

Heirloom Recipes and the Way They Travel Through Time

“Walang Sukat-Sukat”: Teaching by Taste and Tansya

Many Filipino heirloom recipes never get exact measurements. If you’ve ever tried to learn a family dish, you know the drill: “Gaano karaming suka, Ma?” “Yung sakto lang.” “Ilang kutsara ng bagoong, La?” “Yung tama.” In island cooking traditions, this “walang sukat-sukat” method is not laziness; it’s a kind of training. Elders are teaching younger cooks to trust their senses—taste, smell, color, and even the sound a stew makes when it’s nearly done.

Many Filipino heirloom recipes never get exact measurements. If you’ve ever tried to learn a family dish, you know the drill: “Gaano karaming suka, Ma?” “Yung sakto lang.” “Ilang kutsara ng bagoong, La?” “Yung tama.” In island cooking traditions, this “walang sukat-sukat” method is not laziness; it’s a kind of training. Elders are teaching younger cooks to trust their senses—taste, smell, color, and even the sound a stew makes when it’s nearly done.

Imagine a kitchen in Catanduanes. A granddaughter stands beside her lola, watching her cook laing. Lola pours coconut milk by eye, tosses in dried gabi leaves, and only after a while says, “O, tikman mo. Kulang sa alat, ‘di ba?” The girl nods, and together they adjust. That moment—the tiny correction, the shared tasting—is how the recipe transfers, even without a single measuring spoon in sight.

Stories Stirred Into the Pot

Heirloom recipes rarely travel alone; they carry stories with them. In a coastal town in Iloilo, a grandfather might tell his apo how his own mother cooked KBL (kadyos, baboy, langka) on Sundays after church, always with extra sabaw because there were sure to be cousins dropping by. In a small house in Mindanao, a Maranao family might share kuning (turmeric rice) and tiyula itum while talking about how their grandparents prepared the same dishes for pagana feasts long before modern roads cut through their town.

In these island cooking traditions, the question “What makes a recipe heirloom?” has a simple answer: it’s heirloom when it comes with a story, when the dish is inseparable from the memory of who stirred the pot before you.

Recipes That Bend but Don’t Break

Of course, recipes evolve as they move. A family adobo might gain a splash of pineapple juice when someone marries into a household that loves sweetness. A kinilaw might trade tabon-tabon for calamansi and vinegar when the original fruit is hard to find. The important thing is that the dish still feels like home when it lands on the table—recognizable enough that an older relative says, “Ah, parang luto ng lola mo,” even if it’s not exactly the same.

Island-to-Island Flavors: Regional Island Cooking Traditions

Bicol: Coconut Milk, Chiles, and Leaf-Wrapped Memories

In Bicol, island cooking traditions are thick with gata and chili. Take laing or pinangat: taro leaves slowly simmered in coconut milk, often with dried fish or tiny shrimps, sometimes wrapped into small parcels and tied with coconut leaves. It’s the kind of dish that tastes like a rainy afternoon—creamy, a little smoky from the woodfire, with heat that builds gently at the back of your throat.

Families reserve their richest versions for fiestas or big reunions, but a simpler pot might appear on an ordinary Tuesday. In some coastal homes, laing shares the table with sinanglay na isda (fish stuffed with tomatoes, onions, and ginger, then cooked in coconut milk), bridging land and sea in one meal. Articles like Filipino coastal cooking adventures often highlight this Bicolano magic—how the ocean and coconut groves talk to each other through the food.

Visayas: Kinilaw, Kansi, and Seaside Sundays

Across the Visayas, island cooking traditions lean heavily on kinilaw—fresh fish or seafood “cooked” in vinegar or citrus, sometimes with coconut milk, ginger, onion, and chiles. In Siquijor or Negros, kinilaw might mean thin slices of tanguige brightened with kalamansi and a hint of tabon-tabon or biasong, served almost as soon as the fish leaves the boat. On small Visayan islands, it’s not unusual for kinilaw to appear at every major family gathering, from christenings to despedida parties.

Then there’s kansi in Negros—a sour beef soup somewhere between bulalo and sinigang, flavored with batwan and simmered for hours. Served in big bowls on a breezy veranda after Mass, it turns a simple Sunday into a small feast, especially when paired with inasal-style grilled chicken or fresh lato salad.

Mindanao: Turmeric Rice, Coconut Stews, and Pagana Tables

In Mindanao, island cooking traditions reflect a patchwork of Muslim, Lumad, and Christian communities. Among the Maranao, kuning (turmeric rice) is often served at special meals, its golden grains perfumed with lemongrass and spices. It anchors platters of fried fish, palapa (a condiment of sakurab, chiles, and ginger), and stewed meats during pagana, a communal feast where food is both nourishment and offering.

Farther east, in coastal towns of Surigao or Davao, kinilaw takes on new forms: fresh tuna with coconut milk, tabon-tabon, or even grated green mango for extra sourness. The question “How do dishes change from island to island, and why?” is answered in these variations—because the seas, markets, and histories that feed each kitchen are different.

Northern Luzon: Hearty Soups and Mountain Comfort Food

In Ilocos and the Cordilleras, island cooking traditions tilt toward the land. Pinakbet made with bagoong, mountain vegetables, and squash; dinengdeng that balances bitterness and freshness; tinuno (grilled meats and fish) over open coals. In highland areas, native chicken tinola with ginger and sayote warms up cold evenings, while etag (salted, cured meat) appears in slow-cooked stews during special occasions.

These dishes often come out for family gatherings, harvest celebrations, and All Saints’ Day visits, where food doubles as offering and memory. Broader discussions about how foods like lugaw or rice cakes tie into cultural identity—like those explored by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts through its work on intangible heritage—show how even simple dishes become symbols of care and continuity.

Coastal Luzon and Pampanga: Between Sea and Food Capital

On coastal Luzon—Batangas, Quezon, Pangasinan—heavy, sea-scented stews like sinaing na tulingan, pinaksiw na isda, and pakbet with dried fish are common fixtures of island cooking traditions. Kakanin like puto, bibingka, and suman appear at merienda and town fiestas, often doubling as offerings at church or cemetery visits.

And then there’s Pampanga, often called a food capital, where dishes like sisig, bringhe, and rich stews reflect centuries of layered influences. A Kapampangan lola’s kare-kare recipe might include secret ratios of ground rice and peanuts that she passes down “by eye,” while a city-based apo tries to recreate the same flavor after reading about it in guides like Pampanga food trip through the food capital. It’s another reminder that regional dish variations are living, not locked—always adapting to new kitchens, new lives.

Family Cooking Rituals and Kitchen Rhythms

Pre-Fiesta Prep and Long-Table Days

Ask any Filipino about their earliest kitchen memory, and you’ll often hear about fiesta prep. In many island towns, the day before a fiesta turns the entire house into a mini commissary: men scraping coconut and cleaning fish in the yard, women stirring giant kalderos of menudo or kinalderetang kambing, teenagers skewering barbecue, kids tasked with washing banana leaves or arranging plates.

Ask any Filipino about their earliest kitchen memory, and you’ll often hear about fiesta prep. In many island towns, the day before a fiesta turns the entire house into a mini commissary: men scraping coconut and cleaning fish in the yard, women stirring giant kalderos of menudo or kinalderetang kambing, teenagers skewering barbecue, kids tasked with washing banana leaves or arranging plates.

These family cooking rituals are how knowledge passes without anyone calling it a “lesson.” A child learns how to wash rice properly because they’ve been doing it in a big palanggana since they were eight. An uncle learns the exact color kare-kare sauce should be just before the bagoong is served on the side. Pieces like Philippine festivals food traditions show how fiestas tie food to faith and community; here, in the kitchen, you see the quiet backstage work that keeps those traditions alive.

Weekend Markets and Everyday Rituals

Not every ritual is grand. In many Philippine islands, Saturdays begin at the palengke: parents and kids weaving between stalls, inspecting fish eyes for brightness, sniffing mangoes, bargaining over piles of malunggay and pechay. Back home, the family collectively unpacks the haul while an older tita divides ingredients—this for Sunday tinola, that for tonight’s inun-unan (a sour fish stew), the rest reserved for adobo that will stretch over several days.

The soundscape of these kitchens is its own kind of music: the steady chop of onions, the scrape of kawali against stovetop, the occasional “Uy, tikman mo nga ito.” Even the way neighbors wander in for a quick taste or to borrow a cup of sugar feeds into the rhythm. In these daily rituals, island cooking traditions are reinforced not by big speeches, but by repetition, affection, and shared plates.

Street Food and Home Food in Conversation

Street food also plays a role in the story. In coastal cities like Cebu or Davao, families might buy tusok-tusok or grilled isaw for merienda, their flavors blending into the more formal dishes cooked at home. Travelers exploring those scenes through guides like Filipino street food diaries: Manila, Cebu, Davao will see how the street and the home talk to each other—how a sauce from a favorite fishball stand inspires a tweak in a family’s inihaw marinade, or how a beloved barbecue stall’s style eventually becomes part of a household’s own weekend grill ritual.

Changing Times: Modern Kitchens, Migration, and Reinvention

Island Cooking Traditions in City Condos and Overseas Flats

Modern life pulls many Filipinos away from the islands where their family recipes were born. What happens to island cooking traditions when lola’s big clay palayok is replaced by a single induction stove in a studio condo, or when daughters and sons move overseas and cook in tiny shared kitchens?

Often, recipes adapt. Fresh galunggong becomes frozen fish; native chicken becomes supermarket cuts; coconut milk is poured from a can instead of squeezed by hand. Diaspora Filipinos call elders over Viber or Messenger—“Ma, ilang minuto ko pakukuluan yung pata?”—or search online for versions of dishes they vaguely remember, sometimes landing on articles like Filipino coastal cooking adventures or Filipino food culture stories for reassurance that they’re not alone in trying to recreate tastes of home.

Appliances, Supermarkets, and “Shortcut” Dishes

New tools change the feel of the kitchen. Rice cookers hum where open fires used to crackle; pressure cookers cut down the simmering time of pochero and bulalo; blenders make short work of spice pastes that used to be pounded in mortars. Supermarkets and delivery apps make it easier to buy ingredients from all over the country, but they also introduce processed shortcuts—instant ginisa mixes, frozen marinated meats, pre-made sauces.

Some elders worry that these shortcuts erode tradition, but many younger cooks see them as bridges. The key question becomes: “Are we using these tools to avoid learning, or to help keep difficult dishes alive in busy lives?” The broader frame of Filipino cuisine as an evolving, adaptive system—which you see in resources like the Filipino cuisine article on Wikipedia—reminds us that change has always been part of the story.

Reclaiming Ancestral Recipes on Purpose

At the same time, there’s a quiet movement of younger Filipinos actively retrieving ancestral recipes: recording elders on video, scanning old notebooks, or organizing yearly “heritage potlucks” where each cousin cooks one traditional dish. For some families, it’s a way to rebuild connection after years apart; for others, it’s about pride—keeping their small town or island’s flavors alive even if life has moved them far away.

Keeping Island Cooking Traditions Alive

Cooking With Elders, Recording Stories

If you’re lucky enough to still have a lola, lolo, tita, or parent who cooks, one of the best ways to preserve island cooking traditions is simply to ask: “Pwede po ba nating lutuin yung paborito ninyong ulam together?” Then treat the cooking session like both a lesson and a conversation. Take photos of the process, jot down notes, or even record video—not to make content, but to keep a living archive for the family.

Ask questions like “Kailan niyo natutunang lutuin ito?” or “Kanino niyo minana ang recipe na ‘to?” The answers often reveal stories about migration, harvest cycles, fiestas, or even wartime scarcity—stories that might otherwise never come up at the dining table.

Cooking Regional Dishes Wherever You Are

You don’t have to live on an island to honor island cooking traditions. Even if you’re in a landlocked city, you can still attempt laing, kinilaw-style salads (with cooked seafood if raw makes you nervous), Mindanao-style tiyula itum, or Visayan stews using whatever ingredients are available. Imperfect versions are better than letting a dish vanish completely.

Travelers who get curious about these flavors can also support them by seeking out carinderias and small eateries instead of only eating in malls, and by joining cooking demos or market tours where they’re truly welcome. When you travel through food, the goal is to listen and learn, not just “collect” dishes—which is a theme echoed in many Bakasyon.ph stories on food and travel.

Recognizing Food as Living Heritage

More and more, institutions and communities are recognizing traditional dishes as part of intangible cultural heritage—a living practice that deserves safeguarding just as much as songs or rituals. The NCCA and related bodies work with local groups to document and protect practices, from weaving to foodways, as living traditions shared between generations. But inside homes, the work is quieter: making sure there’s always someone younger standing at the stove, watching, tasting, remembering.

How Travelers Can Experience Island Cooking Traditions Respectfully

Eating in Carinderias, Homestays, and Community Tables

For travelers, one of the most meaningful ways to encounter island cooking traditions in the Philippines is to choose smaller, family-run places: coastal carinderias with pots lined up by the road, homestays that include home-cooked meals, or barangay events where visitors are genuinely invited to join the table. These are the spaces where recipes haven’t been overly polished for tourists, where the adobo tastes like someone’s real Tuesday lunch.

When homestays or guesthouses offer cooking lessons or market walks, treat them as chances to learn rather than to perform. Ask permission before filming, be generous with feedback and thanks, and remember you’re stepping into someone’s everyday life—not a set designed around you.

Being Present, Not Just Posting

In a world where every meal can become content, it’s worth asking: “Who is this photo really for?” There’s nothing wrong with taking pictures of beautiful food or kitchens, but try to take a few bites without your phone first. Listen to the way a host describes which fish is best for sinigang on rainy days, or how their mother used to send them to the sari-sari store for missing ingredients. That attentiveness is its own kind of respect.

In a world where every meal can become content, it’s worth asking: “Who is this photo really for?” There’s nothing wrong with taking pictures of beautiful food or kitchens, but try to take a few bites without your phone first. Listen to the way a host describes which fish is best for sinigang on rainy days, or how their mother used to send them to the sari-sari store for missing ingredients. That attentiveness is its own kind of respect.

Seeing Travel as a Chance to Learn, Not Just Consume

Ultimately, island cooking traditions are not attractions; they’re ways of life. When you taste laing in a Bicol carinderia, eat piyanggang manok at a Mindanao feast, or share simple fried galunggong with rice in a homestay by the sea, you’re briefly stepping into someone’s long, ongoing story. Your role is to be a kind guest—pay fairly, be patient, be curious, and carry what you learn into how you cook and eat back home.

When you put all of this together—from coastal kitchens to city apartments, from handwritten notebooks to online calls with lola abroad—you start to see why island cooking traditions matter so much in the Philippines. They’re not just about flavor; they’re about continuity. They answer questions like “Who taught you this?” and “Where did you come from?” with every simmering pot and shared plate.

In the end, these traditions are a living archive of memory, love, and place. Every time you stir a pot the way your lola did, or sit down in a small island eatery and really listen to the story behind the dish, you help keep that archive open—so that future generations can still find themselves, and their islands, in the food they eat.